Andrea Mantegna depicted St. Sebastian at least three times, and each painting is different. In this version, a horse and rider appears in the clouds. Why is it there?

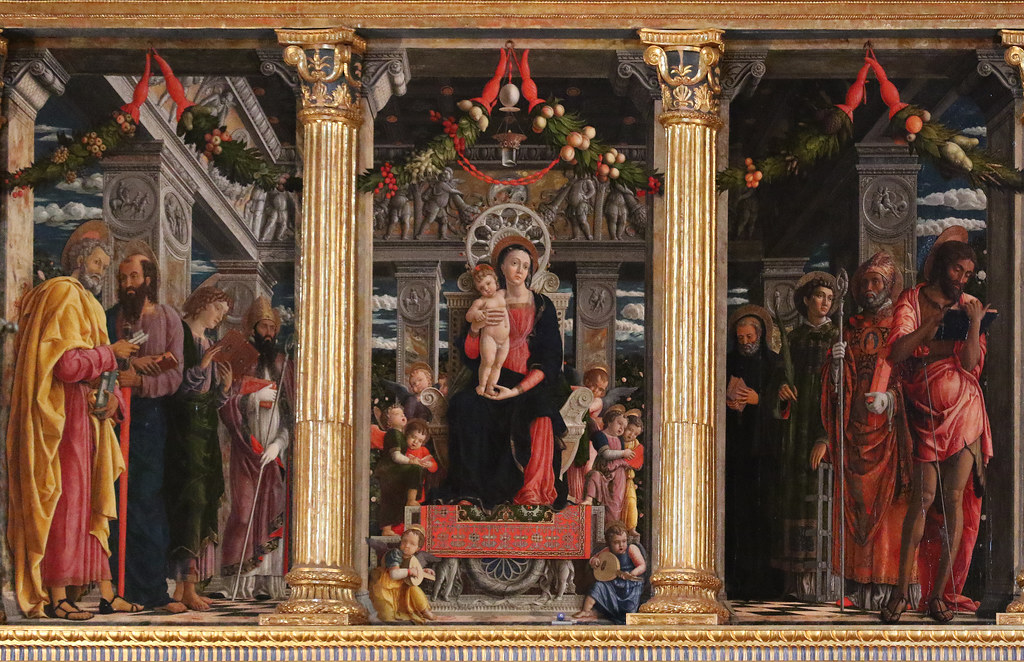

We don’t know who commissioned this painting. At the time (around 1457), Mantegna was in his twenties, living in Verona, and working on his splendid altarpiece for the Benedictine monastery of San Zeno.

San Zeno Altarpiece (c. 1457–60) by Andrea Mantegna (Basilica di San Zeno, Verona)

St. Sebastian would have been an appealing subject for a 15th century patron, in part because of the saint’s connection with the plague.

According to legend, Sebastian joined the Roman army in around 283 AD, rose to the rank of captain, and was selected to protect Emperor Diocletian as part of the elite Praetorian Guard. When the Emperor discovered that Sebastian was converting soldiers and their families to Christianity, he ordered his troops to execute the renegade captain by shooting him with arrows. The archers left him for dead, but a Christian woman secretly treated Sebastian’s wounds and he recovered. He then sought out Diocletian and denounced him for persecuting Christians. This time, the Emperor had Sebastian beaten to death. Church writings from as early as the fourth century refer to him as a saint.

Over time, Sebastian became associated with protection against the plague because he survived an onslaught of arrows: it was thought that plague spread through the air, possibly delivered by arrows shot by the gods.

Plague personified as a woman, fresco in the former Abbey of Saint-André-de-Lavaudieu, France, 14th century1

The Triumph of Death wall painting (c. 1448), artist unknown, Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo (detail)

Photo: Rob Cook 2012

Because of this association with illness, St. Sebastian would have been a focus of prayer in the 15th century. Italy, along with much of the rest of Europe, had been ravaged by bubonic plague in the 1300’s, but the horrifying disease kept returning. Milan, for example, was besieged by plague from 1449-52 2, and Padua was struck in 1456-57. 4

Did Mantegna know the fate of the sculpted rider, doomed to damnation for executing Boethius? Or did he simply appreciate the bold forms: the strong bearded figure, the graceful curve of the horse’s neck? We don’t know, but the Abbey’s bas-reliefs clearly inspired his cloud figure.

Mantegna also slipped anthropomorphic clouds into his Oculus Ceiling (1474) in the Ducal Palace in Mantua, and in the Louvre’s Minerva Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue (c. 1497-1502). I’ll focus on those in a future post.

St. Sebastian

Artist: Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431-1506)

Date: c. 1457-1459

Medium & Support: Oil on Poplar Panel

Size: 68 cm. x 30 cm. (26.8 in. x. 11.8 in.)

Location: Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Online Information:

Carmichael, Ann G., 1 Universal and Particular: The Language of Plague, 1348–1500, Med Hist Suppl. 2008; (27): 17–52, PMCID: PMC2630032

Compostela: The Joining of Heaven and Earth; September 30. 2105, London: Artsymbol.

Hunt, Patrick, Plague and the Medieval Triumph of Death, Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo, Electrum Magazine, April 20, 2012.

St. Sebastian by Andrea Mantegna, Kunsthistorisches Museum website.

St. Sebastian by Andrea Mantegna, Musée du Louvre website.

St. Sebastian, Catholic Online.

Savage, David, Cavallini to Veronese website.

Other Information / Sources:

Arnold, Jonathan J, Theoderic and the Roman Imperial Administration, Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Manca, Joseph, Andrea Mantegna and the Italian Renaissance, New York: Parkstone Press International, 2006.

- She “carries arrows that strike those around her, often in the neck and armpits—in other words, places where the buboes commonly appeared.” Franco Mormando, Piety and Plague: from Byzantium to the Baroque, Truman State University Press, 2007.

- Carmichael.

- Kunsthistorisches Museum website.[/efn_note]

Other Details

Mantegna’s painting is full of features inspired by ancient Greece and Rome, artistic motifs that would have been unusual at the time. He admired the simplicity and elegance of classical forms; for example, the deteriorating arch, with its relief of Victory, is based on the Arch of Septimus Severus in Rome.

Arch of Septimus Severus, c. 203 AD, Roman Forum (detail)

Fragments of columns and statues litter the ground, suggesting that the ancient pagan world has crumbled. Even Sebastian’s body has the cool, smooth texture of antique sculpture. Mantegna signed his name in Greek – “the work of Andrea M” – to the saint’s right.

Horse and Rider

But what is the significance of the horse and rider in the clouds?

The image would have been one that Mantegna saw often as he worked on his altarpiece for the Abbey of San Zeno.

Basilica di San Zeno, Verona

Photo: Zairon: own workA series of twelfth-century bas-reliefs flanks the Abbey’s entrance. They portray scenes from the New and Old Testament, as well as scenes from the life of Theoderic (454-526), King of the Ostrogoths.

Theoderic’s vast empire included Verona, and he built a palace in the city. Although known as a strong leader who promoted scholarship and architecture, in a dark moment of his reign he had ordered the execution of the Christian philosopher Boethius. According to the legend of the Hunt of Theoderic, after the ruler’s death, Boethius’s soul transported Theoderic’s spirit through the air and dropped him into the fiery furnace of Mount Etna.

In this scene at the Abbey’s entrance Theoderic is pursuing a stag, hunting horn in hand, while a demonic figure waits at the far right. The inscription informs us that the king has been presented with a horse, a stag, and a dog, and that he is riding towards Hell, never to return.3Compostela website.

SECRET IMAGES

SECRET IMAGES

Leave a Reply