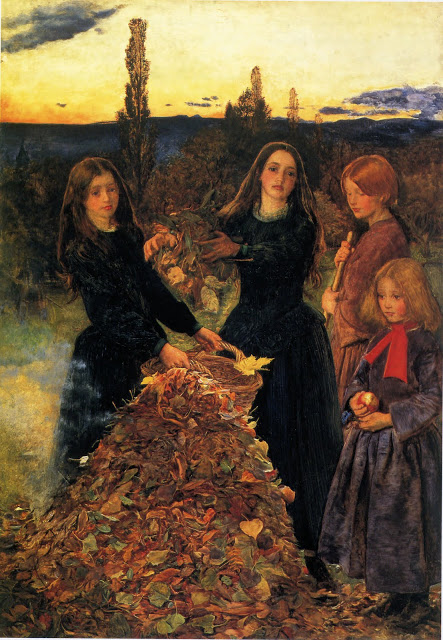

Four girls have been gathering autumn leaves for burning. The sun has set, and their task is almost over for the day. We don’t actually see the fire, but – somewhat strangely – smoke drifts from within the crackling pile. Almost invisible behind the haze is a stooped man at work, holding what looks like a scythe.

Victorian audiences would have noticed the girls’ somber clothing and their pensive expressions in the waning light. (Art critic John Ruskin described this work as “the first instance of a perfectly painted twilight.” 1

Nineteenth century viewers would also have realized that Millais was evoking not only the end of a day, and of a season, but of the end of life.

Next to the right shoulder of the girl on the left is the figure of a reaper. He’s hard to see. His back is to us, and he is swinging his scythe, almost invisible behind the haze of smoke.

(Another interpretation could be that he is holding another tool, like a rake, but that the curve of the girl’s hair suggests a scythe.)

The shadowy laborer underscores the painting’s theme, a subject that Millais returned to often in his work: the transience of life.

Millais wrote that he had “intended the picture to awaken by its solemnity the deepest religious reflection. I chose the subject of burning leaves as most calculated to produce this feeling.” 2

Religious reflection was not the response of the painting’s first owner, a Mr. Eden, who had bought it sight unseen.

As the Magazine of Art reported in 1896, “when the picture reached him he did not like it, and asked the great painter to take it back; but this, Mrs. Millais said, was impossible. He was then told to sit opposite it when at dinner for some months, and he would learn to like it. He tried this, but alas! disliked it more and more. One day a friend…called, saw the picture, was enchanted, and said, “Eden, I will give you any three of my pictures for ‘Autumn Leaves.’ ‘As you are a great friend, said Eden, ‘you shall have it’; and so the picture changed hands.”3

Three years later, Millais explored a similar theme in “Spring (Apple Blossoms).”

Spring (Apple Blossoms) (1859) by John Edward Millais

Again we see young women — including the subjects of Autumn Leaves — in a peaceful landscape. They’re relaxing on the grass and enjoying bowls of curds and cream after gathering flowers. But Millais again reminds us of his enduring message: youth and beauty, like flowers, will soon fade.

The scythe here is far more obvious, almost comically so, with its gleaming blade poised above the girl in yellow.

Autumn Leaves

Artist: John Everett Millais (1829-1898)

In 1848, Millais joined with two other British painters, William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, to found the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. These young men rejected the prevailing view that Renaissance artists such as Raphael represented the artistic ideal. Instead, they advocated painting realistically, from nature, to explore serious moral and social issues.

Date: 1856

Medium & Support: Oil on canvas

Size: 104.3 cm. x 74 cm. (41 in. x 29 in.)

Location: Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester, UK

Online Information:

National Museums Liverpool website’s description of Spring (Apple Blossoms)

Flint, K., 2016. Feeling, Affect, Melancholy, Loss: Millais’s Autumn Leaves and the Siege of Sebastopol. 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, 2016 (23)

Related posts:

Marilyn (Vanitas) (1977) by Audrey Flack

- Ruskin, John (1906). Pre-Raphaelitism: Lectures on Architecture & Painting, &c. London: Dent. p. 220.

- National Gallery of Art, Washington, The Victorians: British Painting 1837-1901, p. 73, 1997.

- John Guille Millais, The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais, President of the Royal Academy, London: Methuen & Co., 1899, p. 291.

SECRET IMAGES

SECRET IMAGES

Leave a Reply