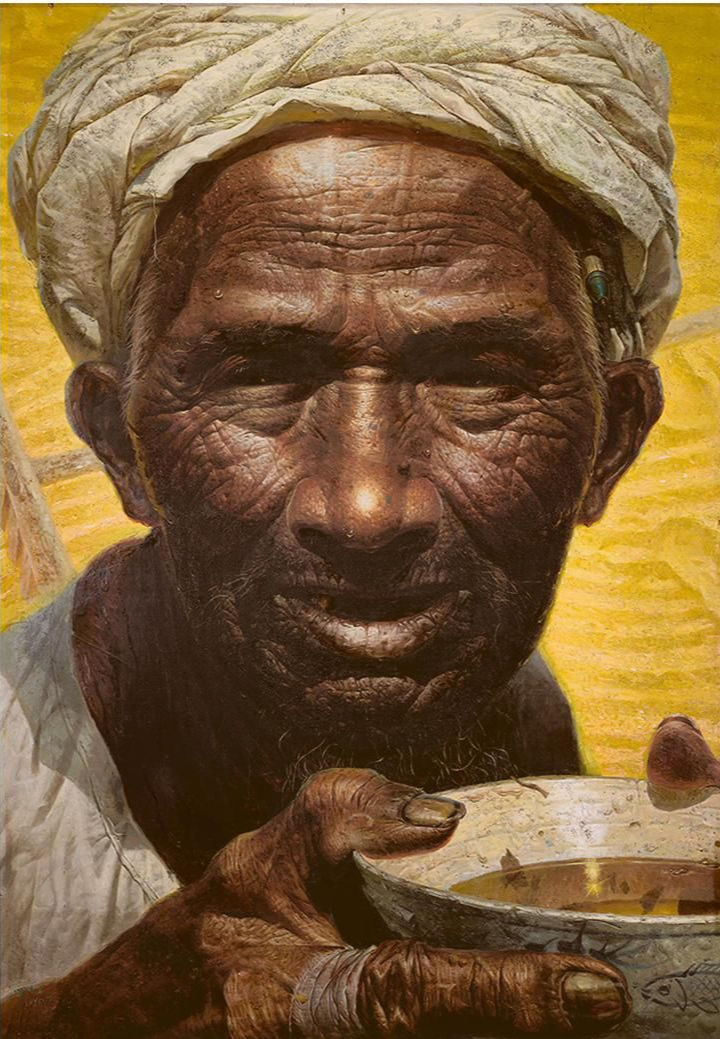

This painting may not look radical, but it was considered extraordinary when it appeared at a 1981 student art exhibition in Beijing. Before it could be displayed, the painter was asked to alter the work to make clear that the elderly farmer could read and write.

The artist, Luo Zhongli, was born in the outskirts of Chongqing, and studied art as a teenager. When Luo was 18, Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution.

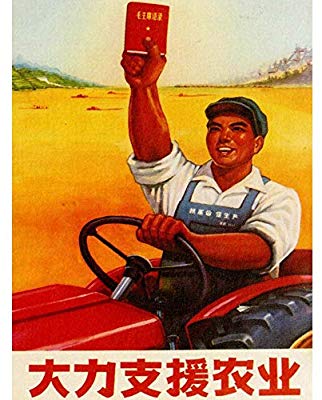

Among many other drastic changes, the government closed all universities and art schools. Artists were expected to produce Social Realist propaganda that glorified the government; those who produced works in a different style were persecuted.

Luo was sent to live with a farming family in the isolated Daba Mountains, where he worked in a steel factory for the next ten years. After Mao’s death the universities reopened, and Luo enrolled in the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute in 1978, at age 30. He was still a student at the Institute when he painted Father in his dorm in 1980, then entered it into the National Youth Fine Arts Exhibition.

At the time, the painting was remarkable for its lack of idealism. Luo declined to paint the glowing, vigorous laborers of Mao’s propaganda.

Father‘s unflinching photorealistic approach reveals every crease and blemish on the farmer’s face, every flaw in his worn teacup.

Luo said he based his weary farmer on the patriarch of his host family in the Daba Mountains, and the respectful portrait hints at the old man’s humanity and simple heroism.

Viewers were also startled by the painting’s scale. It is more than seven feet tall, at the time a size seen as appropriate only for portraits of Mao. “At that time, artists would normally only paint celebrities such as state leaders on that large a scale,” Luo said. “But I dedicated that space to a farmer, symbolizing the commencement of the time of people.”

Two issues concerned the judges, however. First, its original title, My Father, was too personal. In the early years of reform, Chinese society still valued conformity, not individualism, so the work became simply Father.

The exhibition officials were also troubled by the farmer’s uneducated appearance, and asked Luo to place a pen over his ear to demonstrate progress and literacy.

After Luo inserted the pen, the judges allowed the painting into the exhibition, where it won first prize.

Father was one of the pioneering works of the Rustic Realism movement, which focused on the effects of the Cultural Revolution on rural workers, and remains one of the best-known works in modern Chinese contemporary art.

Source: Robert & MeiLi Hefner Collection

Father

Artist: Luo Zhongli (1948- )

After his success with Father and similar works, Luo went on to graduate from the Fine Arts Institute. He taught there for a year, then earned a Master’s degree in Belgium. By the 1990s he had moved away from Rustic Realism and began painting in a more expressionistic way, though farmers are still a favorite subject.

Date: 1980

Medium & Support: Oil on canvas

Size: 227 cm. x 154 cm. (89 1/4 in. x 60 1/2 in.)

Location: National Art Museum of China, Beijing

Online Information:

Ding, Liu and Carol Yinghua Lu, From the Issue of Art to the Issue of Position: The Echoes of Socialist Realism, Part II, e-flux, Journal #56, June 2014.

Luo Zhongli: Capturing Rural Life on Canvas, ChinaToday.com, 11/9/2012.

Luo Zhongli: Capturing Rural Life on Canvas, ChinaCulture.org, 1/9/2013.

Zixuan, Zhang, Agrarian Art, usa.ChinaDaily.com, 3/23/2012.

Other Information / Sources:

Andrews, Julia Frances, Painters and Politics in the People’s Republic of China, 1949–1979, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995, pp. 351–52, 368-76.

Mackenzie, Colin, Katie Hill, Jeffrey Moser, The Chinese Art Book, New York: Phaidon Press, 2013, p. 244.

SECRET IMAGES

SECRET IMAGES

Leave a Reply